People have always told stories in an effort to make sense of experience. Road narratives or roadworks are an American favorite for that process of composing order and meaning into experience.

Drawing from a long history of travel-writing, the road narrative is nomadic and restless. It features ordinary people trying to learn something about themselves and their country, to seek new experiences, to find more and better space, and to meet new people and explore alternative values.

On the road and in their books, we meet everyone from established people getting away from confinement to counterculture dropouts protesting the hypocrisy of the establishment. These people enter the sacred space along the road where they discover adventures and endure trials that are educative, healing, and expansive. Heroes and rogues alike eventually come back home. They sort out what they encountered, and share the insights they reached while gone.

Books written on reentry are as complex as the experiences, cultural symbols, and genre conventions allow, and invite readers into a dialogue on evolving cultural values. Audiences listen and read because the stories are good.

Travels as personification of biblical, mythical and American traditions

Writers such as Thoreau and Whitman are part of the American literary tradition that includes frontier land journeys within the continental United States, legendary sounding travels which take place in union with the Earth, often in an attempt to obtain completeness or rebirth (through the introspective journey) for the characters and writers themselves, Earth and society. The largest contributor and most important trait d’union between the travel literature of the previous century and the 20th century is certainly the writer Henry David Thoreau. In “Walking” (1862), Walden (1854) and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849) he joins the investigation of geographical frontiers with the search for interior borders, with true introspection. With Leaves of Grass (1891/92) by Walt Whitman, the connection with the 20th century continues, especially in “Song of the Open Road”, his best work in the travel narrative tradition. Whitman, like his literary predecessor, exhibits some shamanic tendencies, but unlike Thoreau, is a modern character in him being more sociable (not isolated) and in his acceptance of both urban and rural landscapes as possible spaces through which to travel in search of personal equilibrium.

In the 20th century this quest continues in a modern form, in roadworks, in novels like On the Road (1957) by Jack Kerouac, Blue Highways (1982) by William Least Heat-Moon, and Travels with Charley (1962) by John Steinbeck. The road has remained as frontier, and travels within the American continent have become a way to recreate or reconstruct the frontier experience in terms of modernity. Those who want to write about the frontier in modern terms are the personification of the most recent biblical, mythical and American traditions that are traceable in American everyday life.

The roadworks figure of our times, in the blending of the hunter and the shaman, aims for personal and cultural transcendence through his travels.

The frontier West. Suspects in the Promised Land

The American historian Frederick Jackson Turner saw in his poetical hypotheses the frontier as a “gate of escape” which promoted not only individualism, but personal rebirth (“The Significance of the Frontier in American History”, 1893). This place and time of “buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom”, its socio-geographical concept of the frontier as “a moment where the bonds of custom are broken and unrestraint is triumphant”, between savagery and civilization”, which was once an identifiable space – the West – has been approximated in the 20th century by the road. The act of withdrawal from society remains unchanged in its ability to allow the traveler social- and self-examination, and to remake him or herself.

Henry Nash Smith noted in Virgin Land: The American West as Symbol Myth, 1950, that the frontier West was divided, in the public’s consciousness, into the tedious, “agricultural West” and the “Wild West”, that “exhilarating region of adventure and comradeship in the open air.”Its heroes “were in reality not members of society at all, but noble anarchs owning no masters, free denizens of a limitless universe” – a definition which in its emphasis on “anarchs”, (etymologically, “without a ruler”) freedom, movement and space serves well in providing a partial description of the roadworks characters analized. Smith explains how Puritan New England devotion to social order rendered all frontier emigrants as patent or would-be criminals, since they were “remote from the centers of control”, the church and state. This view seems to be a variant of the earlier European prejudice against wanderers such as pilgrims who were discouraged in their peregrinations not only because they couldn’t then serve as a part of the work force, but because they might also become breeders of royal discontent.

This suspicion towards wanderers is in opposition to the definition proposed for “saunterers” by Thoreau, who traced the word’s etymology to one bound for “Saint Terre”, the Holy Land – one on a pilgrimage. However, society’s suspicion and even hostility toward vagabonds, pilgrims and wanderers is in evidence in almost every roadwork studied, and seems to be particularly virulent in the more recent works of Kerouac, Steinbeck and Heat-Moon. Far from coming to terms with modern-day questers, society, even in the face of its own increasing mobility, continues to exhibit suspicion and hostility towards those outsiders who are not “settled down.”

The West was seen as a place that was out of time. Due to the optimism associated with heading west, it became linked first with progress and then with the American Dream. Christian doctrine contributed to the idea of Westward rebirth, as well. In the American wilderness experience, the Pilgrims who read the Bible saw themselves as the chosen people for the Promised Land – which is responsible for the concept of the American as Adam.

Monomyth

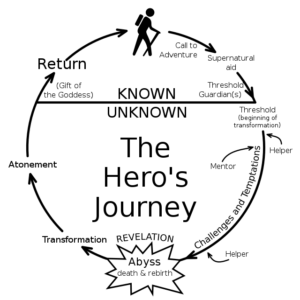

Questers such as Abraham, Moses and Jesus resemble earlier, pre-Christian, mythic, and what Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell would argue are, world-wide figures who quest as well, and whose ubiquitous tale has been named “the monomyth”. The oft-repeated stages of the hero’s journey involve a “separation from the world”, “initiation” or “penetration to some source of power”, and a life-enhancing return to society. In this way, American roadworks exist as fairly recent literary manifestations of an age-old human propensity for myth, perhaps in turn derived from earlier shamans’ accounts of their “travels”.

Farmer vs. hunter

Of the two figures which dominate the American frontier myth – the farmer and the hunter – it was the latter who contributed most to the roadworks figures. In Richard Slotkin’s Regeneration Through Violence, the mythical hunter is searching to unite with his “lost half”, often expressed in the symbolic merging of the hunter with his prey – a kind of marriage-in-death but perhaps more importantly a shaman-like fusion with the natural world. However, in the roadworks figure – a true advancement of the literary model of the American hunter – it is the primacy of the eye and not the gun which allows an imaginative fusion with the landscape and the natural world.

The figure of the shaman

An alternative contributor and bridge to the roadworks character is that of the shaman, a Native figure often ignored in literary discussions. Indians were seen in the emergent American literature as wild, uncivilized, immoral and evil. Indians challenged the view of the new country as Eden and soon came to be endowed, in the minds of whites, with those traits previously ascribed to the wilderness itself, or with traits connected with Satan.

At the center of the Indian culture stands the shaman, who unlike the mythic hunter and roadworks figure undergoes a metaphorical travel only. The shaman is a personal embodiment of the tribe and its quest, in psychological terms, for psychic wholeness. In Jungian terms, he attempts to integrate the conscious with the unconscious, the “male” animus with the “female” anima; in Buddhist terms this is known as the union of yin and yang which manifest Tao, meaning “the road” or “the way”.

If the role of the shaman is to integrate the unconscious and conscious minds, a literary “need” might have developed to integrate society (conscious mind) with the wilderness (unconscious mind) – resulting in a cultural Tao. Such integrative figures have been produced in American literature, and are evident in a line which stretches from (but is not limited to) the writings and personae of Thoreau and Whitman. This character continues in the modern roadwork figure, who in the blending of the hunter and the shaman aims for personal and cultural transcendence through his travels.

The enduring appeal of an alternative vision

Heroes of the road are a diverse group including the academic and the popular students of American culture who retrace previous heroic journeys to rediscover what is very old; and the lost or disinherited looking for answers in the fast lane and in movement itself. Whatever the itinerary, the open road offers freedom, escape, speed, and the liminal state experienced while in motion.

A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man. ~ Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces

Reentry is a crucial stage of every road quest, because it means giving up that liminality; getting off the road is painful in several ways. Returning home means exchanging timelessness for measured limits, the intensity of heightened experience for the boredom of routine. Having been free of obligations for at least a while, the traveler comes back to prescribed roles and duties; with the sanction or excuse for wandering used up or elapsed, pragmatism reasserts its dominance. The daring of speed and power vanish into dullness. What had been sacred space is now zoned commercial; what had been clear and simple is soon muddled and cluttered.

In short, the romance is gone and, in its place, the pain of loss. But in spite of all that, coming home brings its recompense. Just as road pilgrims generally reach their destination, so also protestors proclaim emergent values in opposition to the dominant culture. The dynamics and the difficulties of reintegration become an interpretation of the journey itself: heroes emerge, protestors shape an alternative vision, and those searching for a national or personal identity propose definitions.

Returning heroes share the insights

What remains of the temporary paradise of life on the road is the telling of the story wherein salvation is found not in an escape from daily experiences but rather in a reintegration into what had been left behind. The road hero’s rewards include both the extended release from life back home as well as a return that brings fuller participation in the community of story tellers and readers.

In the communities where reading, discussion, and critiquing take place, new works remake the literary tradition they enter and suggest new ways of looking at personal and national goals. The same community of people who take the trips and shape the visions also write, read, and evaluate the books; that ongoing dialogue also decides what counts artistically. This dialogue with the road has provided reassurance about the cultural identity as well as a way to question social developments and national goals.

Not the End of the Road

The American frontier is not closed. Even since Frederick Jackson Turner’s notice of geographical closure in the 1890s, American writers have continued to document experiences which recreate and redefine the frontier experience. Writers and/or their characters continue to remove themselves from society and travel the American continent in what may be seen as viable alternatives to their socially-defined selves.

The fact that these “fictions” can all be described in religious terms reminds us, I think, not only that we seek to give outsiders some kind of structure, but point to the underlying conflict between the worlds of commerce (time, “history”, society) and of non-commerce, encompassing art, religion, and the self. Perhaps more importantly, the status of being seen as “holy” – with its etymological links to both “whole” and “to heal”, point to how the holy in our society represent both the higher potentialities of humans, and the attempt/ability of those who have attained this status to vicariously “heal” us as well, through the reading of their journeys.

The American frontier is still open, although it may be said to be now expressed more obviously in (driving) time rather than space; that is, roadworks writers, through extended and extensive travels, gain rebirth by dropping from societal, structured, historical time into the “eternal now”, the present-time consciousness of the road. The true quest, which has always been for a new and whole self, remains for those willing to be America’s often-holy outcasts.

In my dissertation «Travels Throughout the American Continent in Search of Identity» (University of Florence, 1999) I focused on prose narratives – fiction and nonfiction by and about Americans – not vacation experiences of tourist diaries but a road genre all of its own combining elements of pilgrimage, quest romance, Bildungsroman, and the picaresque. The aim was to describe the American road narrative, explore its significance and account for its popularity and the road tradition it is creating by examining road narratives from a variety of perspectives: genres with emphasis on social protest, the search for a national identity, journeys of self-discovery, and narrative patterns expressing escape, parody, and metafictional forms.

The dynamics of reentry underscores much that is crucial about the road quest, thus I also considered the difficulties of coming home and finding or creating a meaningful pattern in the telling of the story. Writing about road narratives also required that I too reentered after a long journey of reading and analyzing that began as a few dozen and turned into well over a hundred novels and nonfiction prose accounts.

Angela Maria Carlucci

Angela is a Multilingual Communications Professional | Writer & Speaker | Managing Director | Entrepreneur

“Inspiring and empowering people is what I love doing, for I firmly believe everyone deserves to feel great at any time. Communication is my passion.” You can find her on Twitter @angelacarlucci